The rivers of Norway, Scotland, Canada, and the United States get the imagination rolling. Including Argentina, with its opposite seasons, puts a nice spin on the game. Given these deceptively simple parameters, I hold that only one river stands singly and unassailably for a given month. This is the river, the month is November, and the fish, of course, is the steelhead. Ragging debates attend nearly every other choiceâ€.

The plan was to drive up from Seattle on Saturday morning, once in-country we would purchase the foreign fishing licenses, hit the grocery store, check into a motel, and begin fishing on Sunday morning. The idea was to take it easy on Saturday morning considering the relatively short drive, possibly even sleeping in… yeah right. The short drive obviously meant we had a few extra hours on the way up in which we could check in on the chum salmon that should have been in one of the rivers we would be crossing along the way. They were! We each hooked 3 and landed one a piece. With the coils sufficiently stretched out of our lines we pulled the waders off, put the single hand 9 weights back in the jeep and got back on the road. I think the whole ordeal added an additional 2 hours to our trip.

After nearly choking over the cost of the Canadian license, permits, and whatever else we had to pay to fish, we eventually made it and began fishing the following morning.

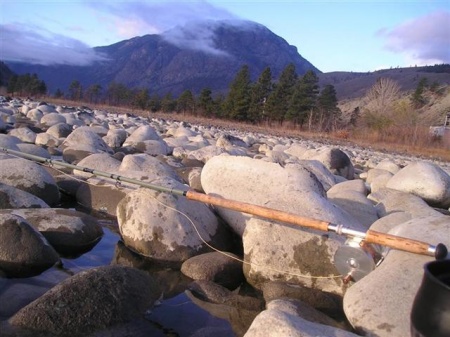

This massive river is known for its difficult wading.

Trey Combs continues to write, “Throat-tightening caution is a fact of life for even the most audacious wader when he balances his life on huge, perfectly smooth rocks well-slimed with algae. A wading staff and stream cleats will reduce the number of times he falls in, and a few pools will call his number nearly every timeâ€.

These fish are believed to “prefer†the floating line, even despite possibly near freezing water conditions. Accomplished BC steelheader Ehor Boyanowsky wrote, “These amazing fish spend two years in the river gorging on the multiplicity of insects then head to the sea for two, three, or even occasionally four years to return as giants that rise to the fly, even the dry fly, in December when the water temperature can be little more than 34 degrees Fahrenheitâ€. The river itself with its distant shallow lies and boulder strewn bottom will definitely help bolster one’s conviction in this floating-line-preference philosophy.

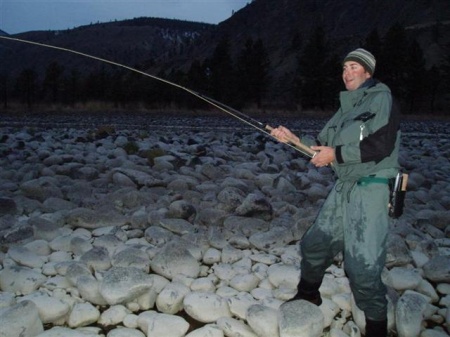

According to the radio, the air temperature was 5(c) BELOW freezing. The water temperature was in the low 40’s (F). The fish took a General Practitioner on a FLOATING line!

Though the fish may not have weighed up to the river’s 15# average, what it was lacking in weight was made up for in power, spirit, and endurance. Any steelhead is a bonus. Exceptional size is merely an additional bonus on top of the initial bonus of the hook-up itself. At least that’s what I told my brother in reference to the 39.5″, 20+ pound hen he’d landed there the previous year.

Harry Lemire is noted for saying, “When I’m on the Dean I think its steelhead are the strongest, but when I’m on this river I think it’s steelhead are the strongestâ€. Ehor Boyanowsky supports Harry’s comment in a Wild Steelhead & Salmon article with, “Laboratory tests reveal that they can hold against a constant current almost twice as long as other strains. Only Dean River fish come close, but they travel a mere 5 to 30 miles in fresh water-not the 200 to 300 of this river’s steelheadâ€.

In my own words I’ll simply say that fish smacked me out of an early morning winter freeze in a matter of seconds and had my heart racing, legs twitching, and teeth no longer chattering as I apparently “glided†over those “smooth rocks, well-slimed with algae†in hot pursuit of that 10 pound bottle-of-lightning 100+ yards down river. All this set to the sweet tune, only a fly fisherman can appreciate, of the high pitched, unmistakable signature scream of a Hardy Bougle!

The beauty of this river like almost all of our west coast steelhead rivers is in its past and its potential, not in its present-day generosity to give up fish. Every fish hooked on this river will be well earned with hours, more likely days, and sometimes even weeks invested into a single pull. These steelhead suffer from the same over harvesting and habitat degradation problems as the majority of the other west coast river’s steelhead.

One last quote from Trey Combs: “During the late 1980’s the run was estimated at “10,000†pieces,†i.e., steelhead. Two thousand steelhead are subtracted from this figure to account for commercial interceptions. The great number of commercial areas in which these fish pass makes this an arbitrary figure, and almost complete guesswork when American waters are factored in. As they enter the Fraser, they encounter an aggressive sport fishery, and hundreds of fish become part of the Province’s punch-card statistics. More than 50 bands of Native British Columbians, mostly of the Sto:lo Nation, have aboriginal fishing rights between the Fraser’s confluence with the Harrison River and Boston Bar. The gill nets set by the Indians for salmon and steelhead typically take 5,000 steelhead, a staggering fifty percent of the escapement. These interceptions-no longer “incidentalâ€- have taken place only on the Fraser below it’s confluence with this river. At this point, if all the interceptions are added up, something like 4 out of every 5 steelhead are already caught before even the first of this river’s steelhead even reaches an anglerâ€. That leaves 1,000 -1,500 fish left to spawn from a run that began in the Pacific at 10,000. Remember my previous comment about potential?